The Nausea isn’t inside me: I can feel it over there on the wall, on the braces, everywhere around me. It is one with the cafe, it is I who am inside it.

Jean-Paul Sartre’s Nausea (1938) came to me at a fortuitous point of my life and seemed to mould itself around my circumstances, like the bleeding light of daybreak on the horizon. I was feeling overly critical, pessimistic, and uninspired, and Sartre’s hand had reached beyond the grave to offer solace of a literary form.

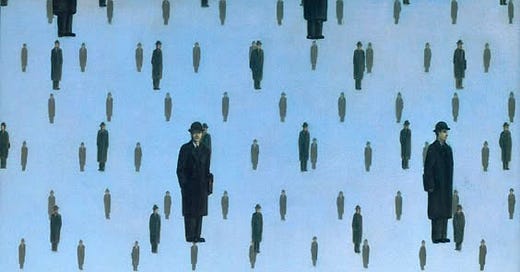

Nausea, to me, reads as a remark on the dangers of overt existential consciousness. Roquentin lives simply and unremarkably, like the every man, but his observations prove woefully analytical because he sees the world in this abstracted way that is deeper than optical. Something on a higher plane. He is acutely aware of connections, objects, relationships, interactions, words said, and stronger still, those unsaid. In being an isolated observer of the world, you are either made privy to the raw and serendipitous beauty of human life in its unabashed artistic coincidence, or in its complete and performative meaninglessness. Roquentin touches on this feeling at the start of the novel:

I know that there’s something else. Almost nothing. But I can no longer explain what I see. To anybody. There it is: I am gently slipping into the water’s depths, towards fear.

Like many others who are torturously afflicted by philosophical interests, existentialism is a fever that seems to enduringly cloud my curious mind. And, Antoine Roquentin is no stranger to its poison. I find myself emulated in the shapes and shadows of Sartre’s words. Roquentin is a struggling writer, alone in the city of Boueville, led entirely by impulse, and over contemplative of the life that surrounds him: “the whole scene came alive for me with a significance which was strong and even fierce, but pure. Then it broke up, and nothing remained”.

He approaches everything with the desire to take it apart and understand it from the inside out. And unfortunately, the head of life itself was most typically at the end of Roquentin’s stick.

When you live alone, you even forget what it is to tell a story: plausibility disappears at the same time as friends. You let events flow by too: you suddenly see people appear who speak and then go away.

Roquentin — proving himself a placid observer of the world, uninterrupted by external chatter, and consumed by his own perspective — descends an existential spiral of dread that accompanies the transcendence and opening of ones mind to all the worldly possibilities. This burgeoning overwhelm brings on psychosomatic symptoms of illness that he calls ‘Nausea’. This Nausea bears a different face and feeling for each person, but I feel as though it embodies this common underlying fear that lurks within the deep recesses of our soul but that we choose to actively ignore — the fear that we are wasting away, living our lives wholly and absolutely wrong, and even time itself will forget us. As if we are stuck in a limbo and falling perpetually short of a discovery that is just beyond the horizon. One that will save us and make it all make sense.

Regardless of how philosophical, cognizant, or intelligent you are, you would be lying if you thought yourself immune to the Nausea. Like a virus, it lays dormant in your body until your consciousness awakens the beast. And from that point on, it never sleeps.

The pressure before the burst; the drag of the undertow before the crashing of the wave. Something is coming but no one is sure of what.

The thing which is waiting has sounded the alarm, it has pounced upon me, it is slipping into me, I am full of it. — It’s nothing. I am the Thing. Existence, liberated, released, surges over me. I exist.

Reading this excerpt made me feel an out-of-body existential pause — a retrospective zoom out on the present moment. I shared in Roquentin’s curiosity and troubles with the purpose of his existence and this epiphany of his seemed to align with the bells that were chiming in my head. That’s it. You are not a victim of existence but an active element of it, and without the spirit of your participation — it is all utterly meaningless.

The awakening of the mind, the removal of the veil. You question and you are freed. The world exudes a different hue, life a richer taste. You are freed from the shackled constructs of modernity and society, but you are most certainly not liberated. Because to know it is not enough. It is action that you must seek. The vast unknown is frightening so many preoccupy themselves with fruitless unfulfilling endeavours, until the distractions lose their edge and the dirt of the Earth welcomes them home again.

Sartre presents a perilous portrait of the over-intellectualisation of life and how it can dispirit you rather than encourage you, which I can vulnerably admit is an innate struggle of mine. I come away from this philosophy classic ruminating on if the cure to the Nausea, or the dread of Existentialism, is either the complete ignorance of it, or the bravery to persist in spite of it.

Love it, well written ❤️

Love your analysis and questions. Sartre’s Nausea is to me Camus’s Absurd. Ignore it or persist despite it? Great question. Camus helped me answer it when he said in The Myth of Sisyphus, “There is a metaphysical honor in enduring the world’s absurdity in a campaign in which we are defeated in advance”. He also said to rebel against it with our defiance and to breathe with it. These simple yet profound notions allowed me to stand up and continue when, not long ago I carried a heavy tragedy. Love that you see this strangeness about our existence and a d understand that before making a choice about what to do with it, the awareness of it, can be creepy, isolating and a burden to carry. You rock!